The best place to start is at the beginning right? I found instructions documenting how to choose a location and take the first steps in making a wilderness camp in the book “Woodcraft” by E.H. Kreps, 1919. Since you don’t want to be starting a project like this in the dead of winter, I thought it would be interesting do installments on how to make and furnish a camp like this. This first section is on choosing a good location for camp and the general requirements thereof. If anyone has experience in this type of construction please comment with suggestions/improvements that you know of.

Building the Home Camp

The first camp I remember making, or remodeling, was an old lumber camp, one side of which I partitioned off and floored. It was clean and neat appearing, being made of boards, and was pleasant in warm weather, but it was cold in winter, so I put up an extra inside wall which I covered with building paper. Then I learned the value of a double wall, with an air space between, a sort of neutral ground where the warmth from the inside could meet the cold from without, and the two fight out their differences. In this camp I had a brick stove with a sheet iron top, and it worked like a charm.

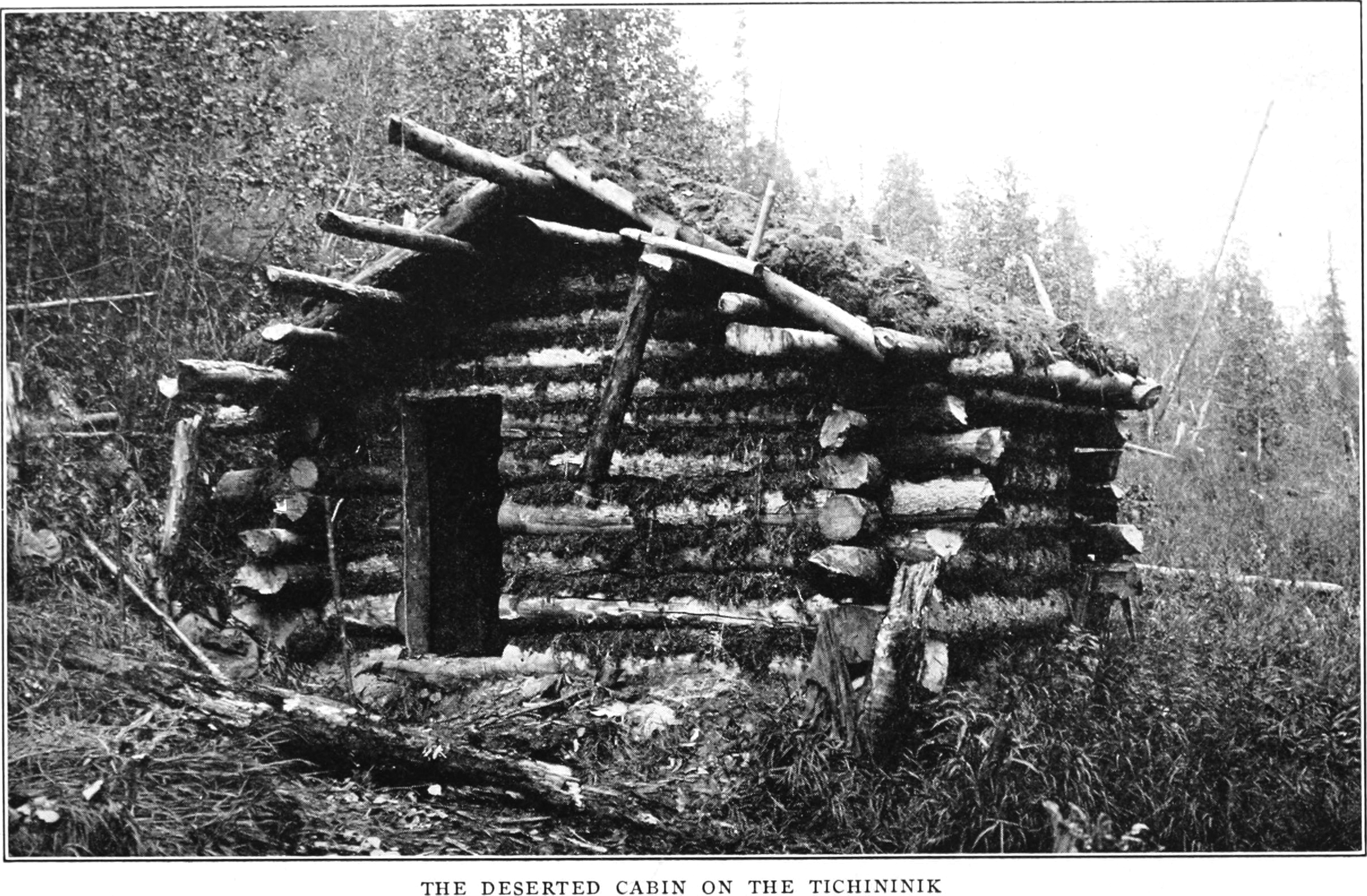

But that was not really a wilderness camp, and while I realize that in many of the trapping districts where it is necessary to camp, there are often these deserted buildings to be found, those who trap or hunt in such places are not the ones who must solve the real problems of camp building. It is something altogether different when we get far into the deep, silent forest, where the sound of the axe has never yet been heard, and sawed lumber is as foreign as a linen napkin in a trapper’s shack. But the timber is there, and the trapper has an ax and the skill and strength to use it, so nothing more is really needed. Let us suppose we are going to build a log cabin for a winter’s trapping campaign. While an axe is the only tool necessary, when two persons work together, a narrow crosscut saw is a great labor-saver, and if it can be taken conveniently the trappers or camp builders will find that it will more than pay for the trouble. Other things very useful in this work are a hammer, an auger, a pocket measuring tape, and a few nails, large, medium and small sizes. Then to make a really pleasant camp a window of some kind must be provided, and for this purpose there is nothing equal to glass.

Right here a question pops up before us. We are going on this trip far back into the virgin forest, and the trail is long and rough; how then can we transport an unwieldy crosscut saw and such fragile stuff as glass? We will remove the handles from the saw and bind over the tooth edge a grooved strip of wood. This makes it safe to carry, and while still somewhat unhandy it is the best we can do, for we cannot shorten its length. For the window, we will take only the glass — six sheets of eight by ten or ten by fourteen size. Between each sheet we place a piece of corrugated packing board, and the whole is packed in a case, with more of the same material in top and bottom. This makes a package which may be handled almost the same as any other merchandise, and we can scarcely take into the woods anything that will give greater return in comfort and satisfaction.

If we are going to have a stove in this cabin we will also require a piece of tin or sheet iron about 18 inches square, to make a safe stovepipe hole, but are we going to have a stove or a fireplace? Let us consider this question now.

On first thought the fireplace seems the proper thing, for it can be constructed in the woods where the camp is made, but a fireplace so made may or may not be satisfactory. If we know the principles of proper fireplace construction we can make one that will not smoke the camp, will shed the proper amount of heat, and will not consume more fuel than a well-behaved fireplace should, but if one of these principles be violated, trouble is sure to result. Moreover, it is difficult to make a neat and satisfactory fireplace without a hammer for dressing the stones, and a tool of this kind will weigh as much as a sheet iron stove, therefore it is almost as difficult to take into the woods. Then there is one or two days’ work, perhaps more, in making the fireplace and chimney, with the added uncertainty of its durability, for there are only a few kinds of stones that will stand heat indefinitely without cracking. On the other hand the fireplace renders the use of a lamp unnecessary, for it will throw out enough light for all ordinary needs.

The good points of the stove are that it can be made by anybody in a half day’s time; it does not smoke the camp, does not black the cooking utensils, gives the maximum amount of heat from the minimum quantity of fuel, and will not give out or go bad unexpectedly in the middle of the winter. If you leave it to me our camp will be equipped with a sheet iron stove. While the stove itself is not now to be considered, we must know before we commence to build what form of heating and cooking apparatus will be installed.

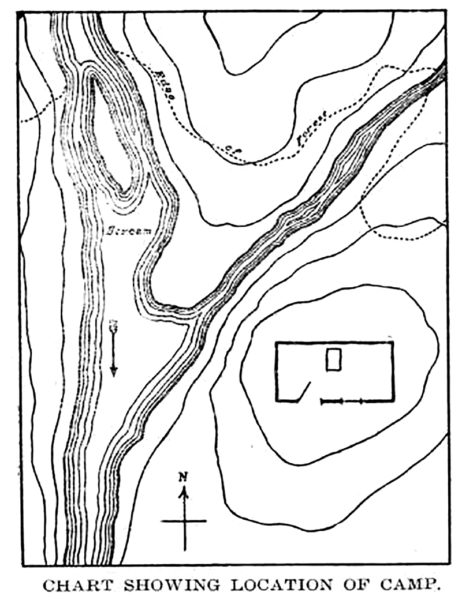

Having decided on which part of the country is to be the centre of operations, we look for a suitable site for our cabin. We find it near a stream of clear water. Nearby is a stretch of burned land covered thinly with second growth saplings, and near the edge of the evergreen forest in which we will build our camp stands plenty of dead timber, tamarack, white spruce, and a few pine stubs, all of which will make excellent firewood. In the forest itself we find straight spruce trees, both large and small, balsam, and a few white birches, the loose bark of which will make the best kindling known. Within three rods of the stream and 50 yards from the burn is a rise of ground, high enough to be safe from the spring freshets, and of a gravelly ground which is firm and dry. This is the spot on which we will construct our cabin, for here we have good drainage, shelter from the storms, water and wood near at hand, and material for the construction of the camp right on the spot.

The first thing to settle is the size of the proposed building. Ten by fourteen feet, inside measurement, is a comfortable size for a home cabin for two men. If it were to be used merely as a stopping camp now and then it should be much smaller, for the small shack is easier warmed and easier to build. I have used camps for this purpose measuring only six and a half by eight feet, and found them plenty large for occasional use only. But this cabin is to be our headquarters, where we will store our supplies and spend the stormy days, so we will make it ten by fourteen feet. There is just one spot clear of trees where we can place a camp of this size, and we commence here felling trees from which to make logs for the walls. With the crosscut saw we can throw the straight spruce trees almost anywhere we want them, and we drop them in places which will be convenient and save much handling. As soon as a tree is cut we measure it off and saw it into logs. These must be cut thirteen and seventeen feet long, and as they will average a foot in diameter at the stump there will be an allowance of three feet for walls and overlap, or 18 inches at each end. We cut the trees as near the ground as we can conveniently, and each tree makes two or three logs. All tall trees standing near the camp site must be cut, and used if possible, for there is always danger that a tree will blow over on the camp some time, if within reach.